Dear God,

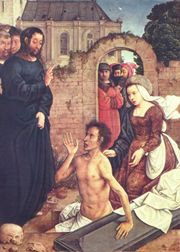

We get to the infamous “raising of Lazarus” story today, which, depending on my mood, either gives me hope or ticks me off (you know, just like everything else I read in a foul mood). In the Gospel of John (11:1-45), we read this:

Jesus … came to the tomb. It was a cave, and a stone lay across it. Jesus said, “Take away the stone.” Martha, the dead man’s sister, said to him, “Lord, by now there will be a stench; he has been dead for four days.” Jesus said to her, “Did I not tell you that if you believe you will see the glory of God?” So they took away the stone. And Jesus raised his eyes and said, “Father, I thank you for hearing me. I know that you always hear me; but because of the crowd here I have said this, that they may believe that you sent me.” And when he had said this, he cried out in a loud voice, “Lazarus, come out!” The dead man came out, tied hand and foot with burial bands, and his face wrapped in a cloth. So Jesus said to them, “Untie him and let him go.”

Now obviously this tale inspires hope for the person who doubts your miracles. Because we can fathom your healing someone with a boo-boo on his leg, or maybe even a leper. But bring a dead man back to life? Now that’s the Cadillac of miracles, one that has skeptics shaking their heads in disbelief.

So here’s my question, God: why don’t you pull off that stunt all the time? How do you decide whom to raise, and whom to leave alone in his stench?

I’m not trying to be disrespectful or facetious. I just don’t understand why you’d bring Lazarus back from the dead and ignore my friend’s three-month-old who couldn’t get off the respirator and start breathing on his own? Lazarus smelled. If I were you, I opt for the baby. And it’s not like the little guy had time to commit that many sins in his three months. That was an innocent life taken from this world with no explanation.

Theologically or philosophically, I know why you can’t raise every Lazarus. My college professor who taught “The Problem of Evil,” Joe Incandela, explained it this way:

If God saved us all the time, then the world would be so unpredictable that it would lack the kind of stability needed for most human activity. This has been called the “cosmic nursery school” view–one does good and gets rewarded, and does bad and gets punished. But if that happened all the time, then God would be constantly intervening in the world in ways that would make any sort of regularity in our lives look impossible. It would also make something like compassion impossible. Compassion (or work for justice or whatever good deed you want to substitute here) requires a regular world, and a regular world means that some people get hurt who don’t deserve to get hurt. I suppose that in a broad sense, this all can be attributed to the Fall. But I think that another reasonable answer is that this is the price of a finite world. Only God is infinite and unlimited. Because of that, any created entity will be corruptible or conflicted in some way. Corruptible or conflicted things tend to rub up against other corruptible or conflicted things, and the result is physical or moral evil.

I keep Joe’s paragraph on my desk and read it whenever something happens like the Virginia Tech shootings or whenever I hear of a young, innocent death, and I’m confused all over again why a God who is supposedly good and loving doesn’t do anything about this stuff.

I also like what Douglas Cootey, fellow blogger, said about Lazarus’s miracle as a response to a post on Beyond Blue where I was griping, as usual, about the Law of Attraction and my problem with people who espouse positive thinking to the exclusion on modern medicine. Douglas wrote:

You shouldn’t discount others’ experiences with positive thinking and faith just because you have not experienced the same. Lazarus was raised from the dead, my brother was not. Does that mean that Lazarus wasn’t raised? Or that faith is a joke because it didn’t work for me? I blamed God for years because of my own disabilities. He wouldn’t take them away for me. All that negative thinking merely made me miserable.

I like this because it leaves room for God to cure however the heck he chooses to—even if his policy makes absolutely no sense to us. Douglas Cootey and Blessed Angela of Foligno, a wife and mother of the fourteenth century who later became a Franciscan tertiary and prominent mystical writer, basically agree on this point: We must believe in God independent of the Creator’s miracles. Writes Blessed Angela:

The way in which a wise person knows something in truth differs from the way a simple person knows only the appearance of truth….Suppose two florins, one of gold and one of lead, were lying in florin because it was beautiful and shiny, but would not know about the value of gold. The wise person, knowing the truth about gold and lead, would avidly go for the gold florin and pay little attention to the lead one. Similarly, the soul, knowing God in truth, is aware and understands him as good, and not only good, but as the supreme and perfect Good.

I suppose right now I’m holding the gold and lead florin with my left hand, and flipping a coin with my right to determine which I should keep and which I should drop at Goodwill. Maybe I’ll go back and take a closer look.

One of my very scripture quotes, Hebrews 11:1, says this: “Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” Which, I think, means that I can ask all the questions I want about Lazarus, and why you chose him over the three-year-old baby of my friend, but that I have to believe in your goodness and love all the time: miracle or no miracle.