John McManamy writes an exceptionally informative article on the types of Bipolar Disorder as defined by the DSM-IV (the shrink handbook). You can get to his article and others by clicking here. I have pasted it below.

John McManamy writes an exceptionally informative article on the types of Bipolar Disorder as defined by the DSM-IV (the shrink handbook). You can get to his article and others by clicking here. I have pasted it below.

There is far more to bipolar than meets the eye. Let’s start with the boring stuff:

The DSM-IV (the diagnostic Bible published by theAmerican Psychiatric Association) divides bipolar disorder into two types, rather unimaginatively labeled bipolar I and bipolar II. “Raging” and “Swinging” are far more apt:Bipolar I

Raging bipolar (I) is characterized by at least one full-blown manic episode lasting at least one week or any duration if hospitalization is required. This may include inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, being more talkative than usual, flight of ideas, distractibility, increase in goal-oriented activity, and excessive involvement in risky activities.

The symptoms are severe enough to disrupt the patient’s ability to work and socialize, and may require hospitalization to prevent harm to himself or others. The patient may lose touch with reality to the point of being psychotic.The other option for raging bipolar is at least one “mixed” episode on the part of the patient. The DSM-IV is uncharacteristically vague as to what constitutes mixed, an accurate reflection of the confusion within the psychiatric profession. More tellingly, a mixed episode is almost impossible to explain to the public. One is literally “up” and “down” at the same time.

The pioneering German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin around the turn of the twentieth century divided mania into four classes, including hypomania, acute mania, delusional or psychotic mania, and depressive or anxious mania (ie mixed). Researchers at Duke University, following a study of 327 bipolar inpatients, have refined this to five categories:Pure Type 1 (20.5 percent of sample) resembles Kraepelin’s hypomania, with euphoric mood, humor, grandiosity, decreased sleep, psychomotor acceleration, and hypersexuality. Absent was aggression and paranoia, with low irritability.

Pure Type 2 (24.5 of sample), by contrast, is a very severe form of classic mania, similar to Kraepelin’s acute mania with prominent euphoria, irritability, volatility, sexual drive, grandiosity, and high levels of psychosis, paranoia, and aggression.

Group 3 (18 percent) had high ratings of psychosis, paranoia, delusional grandiosity and delusional lack of insight, but lower levels of psychomotor and hedonic activation than the first two types. Resembling Kraepelin’s delusional mania, patients also had low ratings of dysphoria.

Group 4 (21.4 percent) had the highest ratings of dysphoria and the lowest of hedonic activation. Corresponding with Kraepelin’s depressive or anxious mania, these patients were marked by prominent depressed mood, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and feelings of guilt, along with high levels of irritability, aggression, psychosis, and paranoid thinking.

Group 5 patients (15.6 percent) also had notable dysphoric features (though not of suicidality or guilt) as well as Type 2 euphoria. Though this category was not formalized by Kraepelin, he acknowledged that “the doctrine of mixed states is … too incomplete for a more thorough characterization …”

The study notes that while Groups 4 and 5 comprised 37 percent of all manic episodes in their sample, only 13 percent of the subjects met DSM criteria for a mixed bipolar episode, and of these, 86 percent fell into Group 4, leading the authors to conclude that the DSM criteria for a mixed episode is too restrictive.

Different manias often demand different medications. Lithium, for example, is effective for classic mania while Depakote is the treatment of choice for mixed mania.

The next DSM is likely to expand on mania. In a grand rounds lecture delivered at UCLA in March 2003, Susan McElroy MD of the University of Cincinnati outlined her four “domains” of mania, namely:

As well as the “classic” DSM-IV symptoms (eg euphoria and grandiosity), there are also “psychotic” symptoms, with “all the psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia also in mania.” Then there is “negative mood and behavior,” including depression, anxiety, irritability, violence, or suicide. Finally, there are “cognitive symptoms,” such as racing thoughts, distractibility, disorganization, and inattentiveness. Unfortunately, “if you have thought disorder problems, you get all sorts of points for schizophrenia, but not for mania unless there are racing thoughts and distractibility.”Kay Jamison in Touched with Fire writes:

“The illness encompasses the extremes of human experience. Thinking can range from florid psychosis, or “madness,” to patterns of unusually clear, fast, and creative associations, to retardation so profound that no meaningful activity can occur.”

The DSM-IV has given delusional or psychotic mania its own separate diagnosis as schizoaffective disorder – a sort of hybrid between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, but this may be a completely artificial distinction. These days, psychiatrists are acknowledging psychotic features as part of the illness, and are finding the newer generation of antipsychotics such as Zyprexa effective in treating mania. As Terrance Ketter MD of Yale told the 2001 National Depressive and Manic Depressive Association Conference, it may be inappropriate to have a discrete cut between the two disorders when both may represent part of a spectrum.

At the 2003 Fifth International Conference on Bipolar Disorder, Gary Sachs MD of Harvard and principal investigator of the NIMH-funded STEP-BD reported that of the first 500 patients in the study, 52.8 percent of bipolar I patients and 46.1 percent of bipolar II patients had a co-occurring (comorbid) anxiety disorder. Dr Sachs suggested that in light of these numbers, comorbid may be a misnomer, that anxiety could actually be a manifestation of bipolar. About 60 percent of bipolar patients with a current anxiety disorder had attempted suicide as opposed to 30 percent with no anxiety. Among those with PTSD, more than 70 percent had attempted suicide.

Depression is not a necessary component of raging bipolar, though it is strongly implied what goes up must come down. The DSM-IV subdivides bipolar I into those presenting with a single manic episode with no past major depression, and those who have had a past major depression (corresponding to the DSM -IV for unipolar depression).

Bipolar II

Swinging bipolar (II) presumes at least one major depressive episode, plus at least one hypomanic episode over at least four days. The same characteristics as mania are evident, with the disturbance of mood observable by others, but the episode is not enough to disrupt normal functioning or necessitate hospitalization, and there are no psychotic features.

Those in a state of hypomania are typically the life of the party, the salesperson of the month, and more often than not the best-selling author or Fortune 500 mover and shaker, which is why so many refuse to seek treatment. But the same condition can also turn on its victim, resulting in bad decision-making, social embarrassments, wrecked relationships, and projects left unfinished.

Hypomania can also occur in those with raging bipolar, and may be the prelude to a full-blown manic episode.While working on the American Psychiatric Association’s latest DSM version of bipolar (IV-TR), Trisha Suppes MD, PhD of the University of Texas Medical Center in Dallas carefully read its criteria for hypomania, and had an epiphany. “I said, wait,” she told a UCLA grand rounds lecture in April 2003 and webcast the same day, “where are all those patients of mine who are hypomanic and say they don’t feel good?”

Apparently, there is more to hypomania than mere mania lite. Dr Suppes had in mind a different type of patient, say one who experiences road rage and can’t sleep. Why was there no mention of that in hypomania? she wondered. A subsequent literature search yielded virtually no data.

The DSM alludes to mixed states where full-blown mania and major depression collide in a raging sound and fury, but nowhere does it account for more subtle manifestations, often the type of states many bipolar patients may spend a good deal of their lives in. The treatment implications can be enormous. Dr Suppes referred to a secondary analysis Swann of a Bowden et al study of patients with acute mania on lithium or Depakote which found that even two or three depressed symptoms in mania were a predictor of outcome.

Clinicians commonly refer to these under-the-DSM radar mixed states as dysphoric hypomania or agitated depression, often using the terms interchangeably. Dr Suppes defines the former as “an energized depression,” which she and her colleagues made the object of in a prospective study of 919 outpatients from the Stanley Bipolar Treatment Network. Of 17,648 patient visits, 6993 involved depressive symptoms, 1,294 hypomania, and 9,361 were euthymic (symptom-free). Of the hypomania visits, 60 percent (783) met her criteria for dysphoric hypomania. Females accounted for 58.3 percent of those with the condition.

Neither the pioneering TIMA Bipolar Algorithms nor the APA’s Revised Practice Guideline (with Dr Suppes a major contributor to both) offer specific recommendations for treating dysphoric hypomania, such is our lack of knowledge. Clearly the day will come when psychiatrists will probe for depressive symptoms or mere suggestions of symptoms in mania or hypomania, knowing this will guide them in the prescriptions they write, thus adding an element of science to the largely hit or miss practice that governs much of meds treatment today. But that day isn’t here yet.

Bipolar Depression

Major depression is part of the DSM-IV criteria for swinging bipolar, but the next edition of the DSM may have to revisit what constitutes the downward aspect of this illness (see Bipolar Depression article). At present, the DSM-IV criteria for major unipolar depression pinch-hits for a genuine bipolar depression diagnosis. On the surface, there is little to distinguish between bipolar and unipolar depression, but certain “atypical” features may indicate different forces at work inside the brain.

According to Francis Mondimore MD, assistant professor at Johns Hopkins and author of “Bipolar Disorder: A Guide for Patients and Families”, talking to a 2002 DRADA conference, people with bipolar depression are more likely to have psychotic features and slowed-down depressions (such as sleeping too much) while those with unipolar depression are more prone to crying spells and significant anxiety (with difficulty falling asleep).

Because bipolar II patients spend far more time depressed than hypomanic (50 percent depressed vs one percent hypomanic, according to a 2002 NIMH study) misdiagnosis is common. According to S Nassir Ghaemi MD bipolar II patients 11.6 years from first contact with the mental health system to achieve a correct diagnosis.

The implications for treatment are enormous. All too often, bipolar II patients are given just an antidepressant for their depression, which may confer no clinical benefit, but which can drastically worsen the outcome of their illness, including switches into mania or hypomania and cycle acceleration. Bipolar depression calls for a far more sophisticated meds approach, which makes it absolutely essential that those with bipolar II get the right diagnosis.

This bears emphasis: The hypomanias of bipolar II – at least the ones with no mixed features – are generally easily managed or may not present a problem. But until those hypomanias are identified, a correct diagnosis may not be possible. And without that diagnosis, your depression – the real problem – will not get the right treatment, which could prolong your suffering for years.

Bipolar I vs Bipolar II

Dividing bipolar into I and II arguably has more to do with diagnostic convenience than true biology. A University of Chicago/Johns Hopkins study, however, makes a strong case for a genetic distinction. That study found a greater sharing of alleles (one of two or more alternate forms of a gene) along the chromosome 18q21in siblings with bipolar II than mere randomness would account for.

A 2003 NMIH study tracking 135 bipolar I and 71 bipolar II patients for up to 20 years found:* Both BP I and BP II patients had similar demographics and ages of onset at first episode.

* Both had more lifetime co-occurring substance abuse than the general population.

* BP II had “significantly higher lifetime prevalence” of anxiety disorders, especially social and other phobias.

* BP Is had more severe episodes at intake.

* BP IIs had “a substantially more chronic course, with significantly more major and minor depressive episodes and shorter inter-episode well intervals.”Nevertheless, for many people, bipolar II may be bipolar I waiting to happen.

Cyclothymia

A likely candidate for the DSM-V as bipolar III is “cyclothymia,” (see article) listed in the DSM as a separate disorder, characterized by symptoms (but not necessarily full episodes of) hypomania and mild depression. One third of those with cyclothymia are eventually diagnosed with bipolar, lending credence to the “kindling” theory of bipolar disorder, that if left untreated in its early stages the illness will break out into something far more severe later on.

Spectrum Considerations

The DSM’s one-week minimum for mania and four-day minimum for hypomania are regarded by many experts as artificial criteria. The British Association for Psychopharmacology’s 2003 Evidence-based Guidelines for Treating Bipolar Disorder, for instance, notes that when the four-day minimum was reduced to two in a sample population in Zurich, the rate of those with bipolar II jumped from 0.4 percent to 5.3 percent. The point is that diagnostic categories are arbitrary, at best. A strong case can be made that the current ones are overly inclusive of unipolar depression at the expense of bipolar disorder. (See The Mood Spectrum and related articles.)

Scientific Theories

The cause and workings of the disorder are terra incognita to science, though there are lots of theories based on encouraging genetics, imaging, and brain science studies. A sampling of what is going on is offered by way of a 2001 Newsletter report:

“Att the Fourth International Conference on Bipolar Disorder in June 2001, Paul Harrison MD, MRC Psych of Oxford reported on the Stanley Foundation’s pooled research of 60 brains and other studies:

“Among the usual suspects in the brain for bipolar are mild ventricular enlargement, smaller cingulate cortex, and an enlarged amygdala and smaller hippocampus. The classical theory of the brain is that the neurons do all the exciting stuff while the glia acts as mind glue. Now science is finding that astrocytes (a type of glia) and neurons are anatomically and functionally related, with an impact on synaptic activity. By measuring various synaptic protein genes and finding corresponding decreases in glial action, researchers have uncovered ‘perhaps more [brain] abnormalities … in bipolar disorder than would have been expected.’ These anomalies overlap with schizophrenia, but not with unipolar depression.“Dr Harrison concluded that there is probably a structural neuropathology of bipolar disorder situated in the medial prefrontal cortex and possibly other connected brain regions.”

Conclusion

So little is actually known about the illness that the pharmaceutical industry has yet to develop a drug to treat its symptoms. Lithium, the best-known mood stabilizer, is a common salt, not a proprietary drug. Drugs used as mood stabilizers – Depakote, Neurontin, Lamictal, Topamax, and Tegretol – came on the market as antiseizure medications for treating epilepsy. Antidepressants were developed with unipolar depression in mind, and antipsychotics went into production to treat schizophrenia.

Inevitably, a “bipolar” pill will find its way to the market, and there will be an eager queue of desperate people lining up to be treated. Make no mistake, there is nothing glamorous or romantic about an illness that destroys up to one in five of those who have it, and wreaks havoc on the survivors, not to mention their families. The streets and prisons are littered with wrecked lives. Vincent Van Gogh may have created great works of art, but his death in his brother’s arms at age 37 was not a pretty picture.

The standard propaganda about bipolar is that it is the result of a chemical imbalance in the brain, a physical condition not unlike diabetes. For the purposes of gaining acceptance in society, most people with bipolar seem to go along with this blatant half-truth.

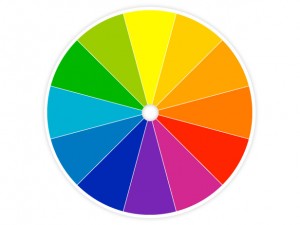

True, a chemical storm is raging in the brain, but the analogy to the one taking place in the diabetic’s pancreas is totally misleading. Unlike diabetes and other physical diseases, bipolar defines who we are, from the way we perceive colors and listen to music to how we taste our food. We don’t HAVE bipolar. We ARE bipolar, for both better and worse.

In one way, it’s akin to being God’s chosen people. As God’s chosen, we are prime candidates for God’s wrath, but even as God strikes the final blow – as the old Jewish saying goes – he provides the eventual healing. In a way that only God can understand, God has bestowed on us a great blessing. Living with this blessing is both a challenge and a terrible burden, but in the end we hope to emerge from this ordeal as better people, more compassionate toward our fellow beings and just a little bit closer to God.