If you ever wonder about that ragged old stranger that you pass on the street every day — and usually go out of your way to avoid — the New York Times’ Dan Barry finds a poignant answer.

If you ever wonder about that ragged old stranger that you pass on the street every day — and usually go out of your way to avoid — the New York Times’ Dan Barry finds a poignant answer.

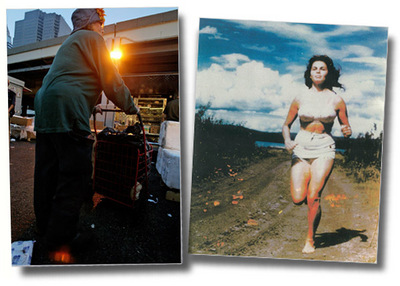

He did a little digging and uncovered the surprising life story of an old woman who called herself Annie (real name: Gloria) who used to haunt the New York fish market — and was also a regular at the Catholic Worker:

She cleaned the market’s offices and locker rooms and bathrooms. She collected the men’s “fish clothes” on Friday and had them washed and ready for Monday. She ran errands for Mr. DeLuca, known as Stevie Coffee Truck, hustling to Chinatown to pick up, say, some ginseng tea. She accepted the early morning delivery of bagels. She tried to anticipate the men’s needs — towels, bandannas, candy — and had these items available for sale.

“If the Brooklyn Bridge could fit in her shopping cart, she would have sold it,” Ms. Fleck said.

Since all this hustling meant carrying around a lot of cash, she tucked away wads of bills in those deep-pocketed pants and other hiding places, including her brassiere. “She tried to look shabby so people wouldn’t give her a hard time” when she left the market, recalled one of her protectors, Joe Centrone, better known as Joe Tuna. “But she was regularly robbed.”

Away from the market, Annie lived as Gloria Wasserman, in the East Village, in a city-owned apartment building that later became part of the Cooper Square Mutual Housing Association. She found joy in her family — a grandson, Travis, in California, and a granddaughter, Chelsea, in New Hampshire — but also sorrow. One of her sons, Kenneth Grinols, died in a fire while squatting in a building in the city. The other, Karl Grinols, struggling with drugs, moved into her apartment at one point, while she slept in a room at the market — “between the mackerel and the salmon,” Ms. Fleck said. But he died young, too, hit by a car in the East Village.

All the while, Annie kept working, rarely missing a day, and gave nearly everything she had to others.

Barbara Grinols…said that Ms. Wasserman often sent as much as $4,000 a month, usually through money orders, to her relations on both coasts. She also routinely sent along boxes of used clothing that she had culled from places like the Catholic Worker’s Mary House, on East Third Street, where she was known as that rare visitor who searched for items that fit others, and who had a gift for using humor and kindness to deflate the tensions arising from hardship.

“She became like a grandmother to dozens of women on the street who had nobody,” said Felton Davis, a full-time Catholic Worker volunteer. Sensing the lack of esteem in a woman beside her, he said, “She would say: `I have just the shirt that you need. I’ll get it for you.’ “

It’s an incredible, beautiful, richly told story. (This is the stuff that Pulitzers are made of, folks.) Read it all.

And remember this woman, and others like her, in your prayers.