I’m not a haggadah junkie. I know many Jews whose shelves are overflowing with numerous versions of the Haggadah – from the traditional Maxwell House to the not-so-traditional Santa Cruz – and whose seders are an amalgam of commentaries, poems, and (alas) responsive readings, from these dog-eared, post- it covered books. Maybe it’s because my family’s seder is geared towards young children; maybe it’s because I prefer discussion to recitation; or maybe because I think there’s more than enough meaningful text to fill a seder without any extra thrown in; but I’ve always been of the opinion that when it comes to haggadot, less is more.

Nevertheless, when I was offered a copy of the New American Haggadah to review, I was elated. I’d just heard Nathan Englander, the brilliant writer who translated the Haggadah, on Fresh Air days before I received the book. On the show, he talked to Terry Gross about his own background as a no-longer-Orthodox Jew with a strong yeshiva education. He described the seriousness with which he approached the project, spending years with his hevruta, pouring over every word choice to try to capture the “rhythm, clarity, communication, meaning..(and).. intent” of the original text. Listening to the few examples quoted in the interview, from his daring translation of Eloheinu, Melech HaOlam to his midrashic turn on the plague of choshech, I couldn’t wait to see the rest. (Did I pique your curiousity? Check out the interview. Or better yet, the haggadah itself.)

Nevertheless, when I was offered a copy of the New American Haggadah to review, I was elated. I’d just heard Nathan Englander, the brilliant writer who translated the Haggadah, on Fresh Air days before I received the book. On the show, he talked to Terry Gross about his own background as a no-longer-Orthodox Jew with a strong yeshiva education. He described the seriousness with which he approached the project, spending years with his hevruta, pouring over every word choice to try to capture the “rhythm, clarity, communication, meaning..(and).. intent” of the original text. Listening to the few examples quoted in the interview, from his daring translation of Eloheinu, Melech HaOlam to his midrashic turn on the plague of choshech, I couldn’t wait to see the rest. (Did I pique your curiousity? Check out the interview. Or better yet, the haggadah itself.)

The Haggadah is simply magnificent. The translation turns the English “side” of the service, which has always felt clunky and awkward to me (“Wherefore is this night distinguished from all other nights?”) into poetry. It’s a translation finally worthy of sharing the page with the Hebrew. Which is so, so important for those of us who can’t engage meaningfully with the text in the original.

I could blather on about why I love Englander’s translation. (In fact, I did just that when I got to go out for drinks with him after his reading at a local bookshop.) But I’m going to trust that a glimpse of one of my favorite pages will give you a far better sense of the haggadah than all my blathering. I’ll also share a little bit of what I learned about these pages from interviewing Englander and the editor, Jonathan Safran Foer. (I know what you are thinking. Right?) Then, I’ll tell you about the giveaway I scored for you, my beloved readers.

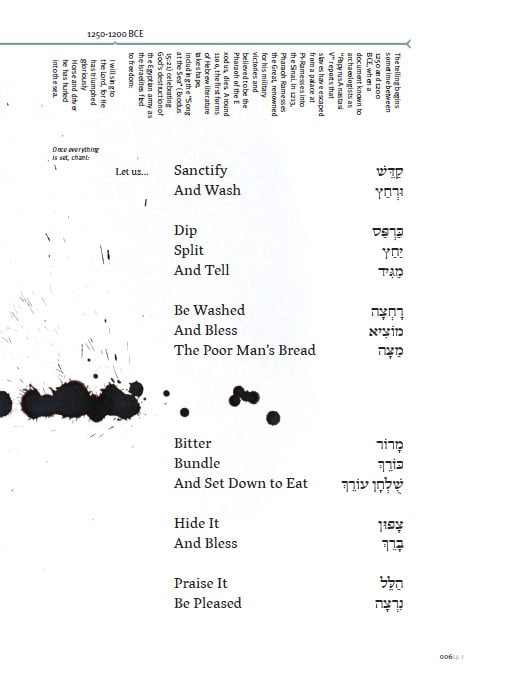

These two pages appear side by side, just after candle lighting, to introduce the steps of the seder:

I asked Nathan about this translation. He spoke about the tension between translating literally and capturing the artistic essence of the original. “”This is a poem in Hebrew, so I wanted it to read like a poem in English.” But, he explained, the words he chose also had to help illustrate the ceremony of the seder. “They are words, with specific meaning, but they are also touchstones – they represent actions and ideas. If you only knew the meaning of the words, that wouldn’t be enough to understand. You’d still have to ask.”

You can see a section of the timeline which runs along the top margin of the entire Haggadah. According to Safran Foer, “there’s been some confusion about the timeline. It’s not a timeline of Jewish history, but a timeline of the Exodus story and how it’s presented in Jewish history and world history. It’s arguably one of the best known stories. To me, the timeline inspires a kind of awe, which I think is an appropriate reaction to the Haggadah.”

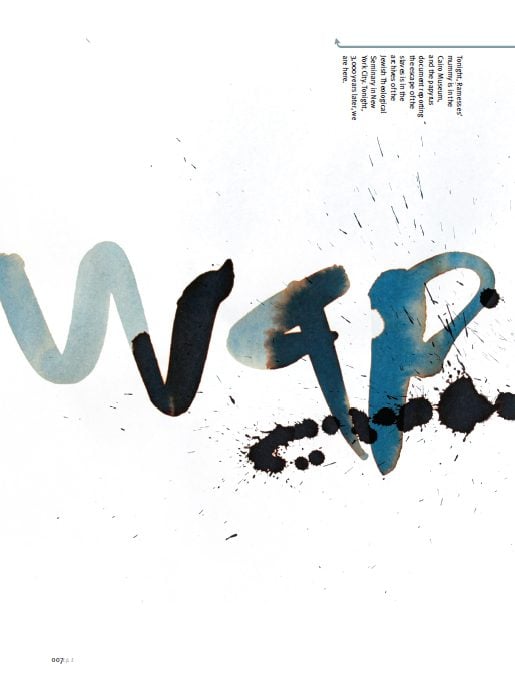

On the opposite page, the illustration is actually the word Kadesh written in Hebrew handwriting dating back to 1200 BCE. Safran-Foer explained that the graphic artist, Oded Ezer, used the timeline to inspire his art. “On each page he would look at… what the timeline was referring to and researched Hebrew typography for that period. He used that as the basis for the design.”

What you can’t see on this page are the four commentaries that also run throughout the book, written by Jeffery Goldberg, Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, Nathaniel Deutsch, and Lemony Snicket. (Yes, that Lemony Snicket. “For the kids,” explained Safran Foer. “He knows that age group better than anyone.”) While they offer some interesting insights, I admittedly wouldn’t recommend this Haggadah for the sake of the commentary. It’s the text itself that makes this a transformative work. Which I think is more or less how it should be.

I doubt I’ll be using this Haggadah at the seder I have with my 6 and 8 year old daughters, who will not swoon when they come to the translation of Tam as “The Artless One.” (And wait until you see what he does with the words Barukh Hamakom.) But it’s been by my bedside since I received it, and reading through a few pages a night has been part of my own spiritual preparation for Passover. (Which in past years has consisted mostly of…..vacuuming.)

Would you like a copy of your very own? (You don’t even have to answer.) Little, Brown and Company has graciously offered THREE copies to homeshuling readers. (Between the interviews and the giveaway I’m beginning to think they have confused me with some other blogger.) All you have to do to enter is leave a comment below (scroll way down!) However, the winners will not be selected (at random, of course) until I have at least 100 comments. The deadline to enter is Tuesday, March 20 – noon, Massachusetts time. So, please, share a link, spread the news. Otherwise, I may never get to have a martini with a famous author again.