At this late point in summer, the controversy about the crucifixion scene in Madonna’s Confessions Tour–when Madonna sings “Live to Tell” while up on a cross, arms outstretched, with scenes of poverty in Africa flashing behind her–has escalated to a cacophony. (Watch the scene here.)

At this late point in summer, the controversy about the crucifixion scene in Madonna’s Confessions Tour–when Madonna sings “Live to Tell” while up on a cross, arms outstretched, with scenes of poverty in Africa flashing behind her–has escalated to a cacophony. (Watch the scene here.)

I feel quite alone in applauding Madonna’s act. While I received many letters of thanks for my NPR commentary, “Madonna’s Cross Raises Thorny Questions,” I’ve also endured a good amount of venom for my argument: that Madonna is embodying a powerful and important ideal by asserting the right for a woman to image Christ.

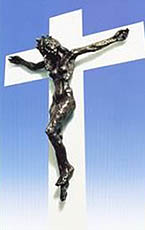

Just about everyone–including both the Catholic Church and Church of England–has called Madonna’s move “offensive,” in much the same way Christian leaders have responded to past attempts to put a woman in Jesus’ place. Perhaps most famous of all these attempts–prior to Madonna’s, at least–is Edwina Sandys’s four-foot, bronze statue, Christa (right), which depicts a bare-breasted, wide-hipped woman nailed to the cross. The sculpture was sent on a decades-long tour around the world that inspired outrage wherever it went (most notoriously at St. John’s Cathedral in New York), until it found a final resting place at Yale Divinity School, where it can still be seen today.

Just about everyone–including both the Catholic Church and Church of England–has called Madonna’s move “offensive,” in much the same way Christian leaders have responded to past attempts to put a woman in Jesus’ place. Perhaps most famous of all these attempts–prior to Madonna’s, at least–is Edwina Sandys’s four-foot, bronze statue, Christa (right), which depicts a bare-breasted, wide-hipped woman nailed to the cross. The sculpture was sent on a decades-long tour around the world that inspired outrage wherever it went (most notoriously at St. John’s Cathedral in New York), until it found a final resting place at Yale Divinity School, where it can still be seen today.

Although Christ is often depicted artistically as being of virtually any race–African, Asian, Latino, Caucasian–the idea of seeing Christ on the cross as a woman sparks automatic and seemingly universal rejection. Perhaps this is not surprising, given the dominance of the male form and male language about God, which has been the norm throughout Western history. And, of course, there’s that pesky fact that Christians are always mentioning about Jesus–that, of course, he was a man.

But feminist theologian Sandra Schneiders explains that when it comes to speaking about and imaging the divine, our society suffers from a “paralysis of the religious imagination.” Even though most Christians believe that all portrayals of God, even those of Jesus, are metaphorical–and therefore portraying the divine as feminine is well within the boundaries of the tradition–Schneiders writes, with sadness, that “to imagine God or speak to God as feminine does not simply change the God image for these people; it destroys it.”

Is this, then, the problem with Madonna climbing up onto the cross? Do people believe she is out to destroy for believing Christians the divine figure that is Jesus? Are we witnessing a society-wide paralysis of the religious imagination as Madonna’s tour moves from city to city across the globe? If so, the controversy betrays the need for a long-overdue reflection among believers about why it is so utterly problematic, offensive, and even blasphemous to allow a woman’s body to image the divine, and what that says about society’s valuing–and devaluing–of women’s bodies.

No doubt Madonna’s crucifixion scene is subversive and outrageous–but it is in no way gratuitous. It’s subversive only because our ability to imagine the divine is impoverished by the fact that we don’t allow for these images to embody gender differences. And it’s outrageous only because it is considered offensive and even blasphemous that a woman, regardless of who she is, should step up and take her rightful place on the cross.

Despite the seemingly-universal criticism she’s getting, I applaud Madonna for her daring. She is accomplishing a task that I and many others have attempted: offering her own body on the cross. And she’s doing it with a degree of success never before seen in Western culture, traveling the world before hundreds of thousands of people every night repeating her powerful example in city after city. And newspapers and magazines everywhere are reproducing this image, not realizing, I suppose, that they are bringing what has long been forbidden contraband to the eyes of people all over the world, most of whom have never had the opportunity or even the desire to view a woman on the cross.

So thank you, Madonna, for providing the world with this extraordinary, historic opportunity.