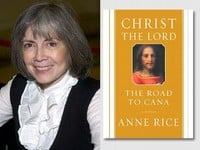

I recently read Anne Rice’s memoir (Called Out of Darkness: A Spiritual Confession

); the good folks at Beliefnet got me in touch with Anne for an interview — and I’m most grateful for her time and for her answers. Here is the first of two sets of questions:

Your question is a challenging one, but I was not lacking at

Your question is a challenging one, but I was not lacking at

the sensory level when I returned to the church. Rather the “going

home” was all the easier because the sensory elements of Catholicism

were still richly present, and they attracted me as much as an adult,

as they had attracted and satisfied me as a child. But my life was

full of sensory elements at the time, especially paintings by my

husband, religious statues that I had collected, numerous photographs

of gorgeous places I had visited, etc. The underlining key is this:

Catholicism does embrace the senses, and has never sought to “purify”

its sensuous elements, and for this reason I feel very comfortable in

my childhood church. The mystery of the Eucharist which drew me back

to the church is enshrined in sensuous elements: the golden tabernacle,

the ritual of the Mass, the incense, bells, the ritual of receiving

communion etc. I should add that as a child, I was shaped by this

sensuality, and it marks all my work.

In reading your story I was struck by a spatial pattern: in New

Orleans as a child you had faith, out of New Orleans you lost your

faith, and when you returned to New Orleans your faith was re-awakened.

Can you reflect on the significance of “space” (even “sacred space”)

for your reconversion?

There is no doubt that my return to New Orleans heavily

influenced me to return to my church. I like to believe, however, that

the conversion would have come no matter where I was. But I think in

going home to New Orleans in 1988, I was in a way searching for my lost

faith. I thought I was seeking my lost city and my lost childhood, but

I was also a pilgrim wandering back to the shrines of childhood to pray

for guidance, whether I admitted it to myself or not.

want to discuss, is the response of Stan and your son Christopher to

your conversion to the Church. What were the themes of your

conversation with Stan? What are the themes of your continuing

conversation with Christopher?

I had no real conversation with either Stan or Christopher

about going back to the church, except for the notable exchange with

Christopher mentioned in the book, in which I asked if he believed in

God and he told me that he did. I avoided discussing the matter with

them because the matter for me was of the utmost importance and I did

subject. After my return, I simply told them that I had done it. When

Stan sought from time to time to engage me in light argument about it,

something that I think would have amused him, I simply did not respond.

I made up my mind I would not argue faith with him. I didn’t think

that Stan was well informed enough to discuss the matter, and I

protected myself from casual argument by simply not doing it.

Christopher occasionally mentioned it but I don’t recall an intense

conversations. He knows how proud I am of him and of his writing and

his life, and the matter does not divide us. Occasionally he comes to

Mass with me, at my request.