In my last post, I argued that the resurrection of Jesus, though not proving that he was God, did vindicate him and his ministry. Through the lens of Easter, the early Christians began to see things about Jesus that they had not really noticed before. Or if they had noticed, they simply accepted these things as peculiar anomalies. Yet the resurrection both sharpened their vision and deepened their insight into the true nature of Jesus.

Jesus Spoke with God’s Own Authority

For example, though Jesus found his place within the prophetic tradition of Israel, and though he was considered a prophet by his Jewish contemporaries (for example, Mark 8:28), Jesus did not echo the prophetic claim to authority: “the Lord says.” This phrase, which appears more than 700 times in the Hebrew prophetic writings, is never heard on the lips of Jesus. He simply spoke authoritatively, as if he were the Lord himself. During his earthly ministry this directness stunned those who heard him and augmented his popularity (see Mark 1:27-28). But, after his resurrection, the followers of Jesus began to see his authority in a new light. The believed that he spoke as if he were the Lord because, in fact, he was the Lord.

Jesus Forgave Sin as if He Were God

Similarly, Jesus had the audacity to forgive sin, not sins done against him, but sin in general. Before healing a paralyzed man, for example, Jesus said to him, “Son, your sins are forgiven” (Mark 2:5). The Jewish scribes who heard him were incensed, “Why does this fellow speak in this way? It is blasphemy! Who can forgive sins but God alone?” (v. 7). Jesus explained that he, as the Son of Man, had this authority (v. 10). So, either God delegated to the human Jesus that which God alone could do, forgive human sin, or Jesus forgave sin because he was actually God in human form. The early Christians took this second option.

Jesus Assumed the Character of Divine Wisdom

According to many New Testament scholars (and scores pseudo-scholars), Jesus was a “sage,” a wise man in the tradition of the Jewish wisdom teacher. There is no doubt that Jesus filled this role to some extent, though it must be balanced with Jesus’ prophetic ministry as well. (Photo: The cover of a book by Ben Witherington III, Jesus the Sage: The Pilgrimage of Wisdom. This is a sane, careful examination of early Christian belief about Jesus and Wisdom.)

But Jesus was more than a mere sage. As I showed earlier in this series, Jesus spoke, not just as a human inspired by God’s wisdom, but also as Wisdom herself. (Remember: Wisdom in Jewish tradition is portrayed as a female companion of the Lord.) The early Christians took this ball and ran with it, picturing Jesus as the embodiment of Wisdom (see, for example, John 1:1-18; Colossians 1:15-20; Hebrews 1:1-14). He was God’s Word/Wisdom incarnate (John 1:14).

Jesus Claimed Unprecedented Intimacy with God

Jesus startled both his followers and his opponents by speaking of his relationship with God in extraordinarily intimate terms. As far as we can determine, nobody before Jesus had the audacity to address God as “Father” in prayer, or to refer to God as “my Father.” Yet Jesus did so with unsettling nonchalance. Remember his prayer in Matthew 11:25-27:

I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and the intelligent and have revealed them to infants; yes, Father, for such was your gracious will. All things have been handed over to me by my Father; and no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.

It’s only a small step from there to what Jesus said in John 10: “What my Father has given me is greater than all else, and no one can snatch it out of the Father’s hand. The Father and I are one” (vv. 29-30). Thus, in the prologue to his gospel, John describes Jesus, not only as the Son of God, but also as “God the only Son” (John 1:18).

Though it was surely possible for Jesus, as a mere mortal, to have deep intimacy with God his Father, the way he spoke of God suggested that this relationship went beyond intimacy to identity of some sort. And yet Jesus still prayed to God his Father. Thus Jesus, as God the Son, was not the same being as God the Father. In the New Testament we find the seeds that later sprouted into full-grown Trinitarian theology.

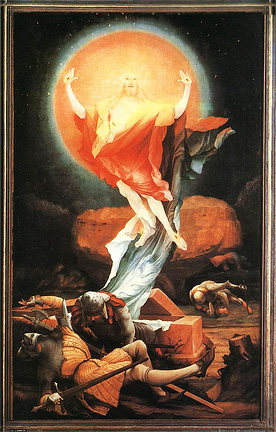

The Death and Resurrection Showed that Jesus was the Divine Savior

As I explained above, the early Christian confession of Jesus as Savior soon led the conclusion that he was God. The syllogism is an obvious one:

Jesus, through his death and resurrection, saved us from our sins.

Therefore he is the Savior.

But God alone is the Savior.

Therefore, Jesus is God.

Of course you don’t find this exact syllogism in the pages of the New Testament. But its logic convinced the early Christians, most all of whom were monotheistic Jews, that Jesus was not just a human Messiah, but God with us, Emmanuel. (For the record, this same logic motivated later Christological inquiry as well. The fact that Jesus saved humanity meant that he had to be both God and human.) Moreover, the early Christians, who were monotheistic Jews, found it natural to worship Jesus because of what he had accomplished as the Savior and Lord.

In my next post I’ll return to the theory that Jesus was divinized under the influence of Greco-Roman pagan culture. Then I’ll add a few closing thoughts as I wrap up this series.