Introduction to Pontius Pilate

If we’re going to understand the Roman perspective on the death of Jesus, we need to know something of the Roman man who was legally responsible for his crucifixion: Pontius Pilate. Traditionally, Pilate has been seen by Christians in relatively positive terms, as one who really didn’t want to crucify Jesus but who did so because he was compelled to by the Jewish leaders and crowds. This image of Pilate, that seems to emerge from the New Testament gospels, doesn’t fit with what we know about Pontius Pilate from historical sources, including the gospels themselves. Let me survey this evidence briefly.

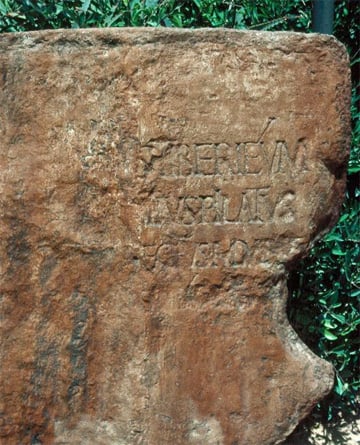

Pontius Pilate was the governor of Judea from 26-37 A.D. An inscription discovered in the ruins of a Roman theater in Caesarea reveals that Pilate’s official Roman title was “prefect” (Latin, praefectus). In this role he was ultimately responsible for all matters in Judea, including judicial and financial affairs. Pilate governed from the provincial capital of Judea, Caesarea (Maratima), a city on the Mediterranean coast, about 75 miles northwest of Jerusalem. He would make the trip to Jerusalem only when necessary. Pilate was accountable to the governor of Syria, through whom he was ultimately subservient to the Roman Emperor. (Photo: This inscription identifies Pontius Pilate as the [Praef]ectus Iuda[eae]).

Pontius Pilate was the governor of Judea from 26-37 A.D. An inscription discovered in the ruins of a Roman theater in Caesarea reveals that Pilate’s official Roman title was “prefect” (Latin, praefectus). In this role he was ultimately responsible for all matters in Judea, including judicial and financial affairs. Pilate governed from the provincial capital of Judea, Caesarea (Maratima), a city on the Mediterranean coast, about 75 miles northwest of Jerusalem. He would make the trip to Jerusalem only when necessary. Pilate was accountable to the governor of Syria, through whom he was ultimately subservient to the Roman Emperor. (Photo: This inscription identifies Pontius Pilate as the [Praef]ectus Iuda[eae]).

Pilate does not figure prominently in first-century Roman histories, a fact that suggests that he was a relatively insignificant leader. Moreover, the assignment to govern Judea was no plum, and some of those who served in Pilate’s position were known to complain about it. Not only was it potentially a dead-end job, but also it was fraught with complications.

The complications had largely to do with what the Romans would see as the peculiarities and propensities of the Jews. The peculiarities were, by and large, Jewish religious sensibilities that put them at odds with Roman norms. Jews, for example, did not follow the Roman model in welcoming all sorts of gods into their pantheon. On the contrary, Jews would die for their belief in one and only one God. Jewish propensities had to do with general unrest and fairly regular attempts by some Jews to rebel against Roman rule. When one became prefect of Judea, one could expect trouble.

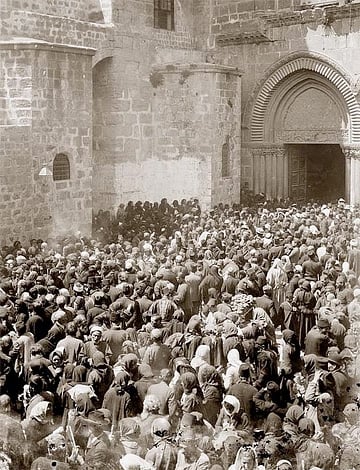

Pilate’s inability (or unwillingness) to respect Jewish sensibilities is seen in an event recorded by the Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities 18.3.1). Unlike previous governors, when Pilate took charge, he brought images of Caesar into Jerusalem in order to display them. This enraged the Jewish population, who took this as a violation of their law and as an insult. Multitudes of people traveled to Caesarea in order to ask Pilate to remove the images. At first he refused and, when the petitioners persisted, he was prepared to kill them. But when they showed themselves willing to die rather than have their laws violated, Pilate finally relented. In another instance when he offended Jewish sensibilities, Pilate did not show mercy, and those who protested were slaughtered by soldiers under Pilate’s command (Antiquities, 18.3.2).

The New Testament actually confirms this picture of a cruel Pilate. In Luke 13:1 we read, “At that very time there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices.” We don’t know anything else about this incident. But it appears that, for some reason, Pilate killed some Galileans who had come to the Jerusalem temple in order to offer sacrifices to God. Yet, not only did Pilate have them killed, he also had their own blood mingled with the blood of the animals they had sacrificed. Talk about adding insult to injury!

The first-century Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria once wrote a letter to Caesar, in which, among other things, he complained about the harshness of Pontius Pilate. Philo blames Pilate explicitly for: “briberies, insults, robberies, outrages, wanton injustices, constantly repeated executions without trial, and ceaseless and grievous cruelty.” (Legatio ad Gaium, 301-302). Even granting Philo’s bias against Pilate, this text doesn’t reflect well upon Pilate’s governorship. In the end, he was removed from office by the Syrian governor, Vitellius, though we don’t know exactly why.

But what about the image of Pilate as the reflective leader who is reticent to kill Jesus, and who even converses with Jesus about the nature of truth? I’ll address this picture in greater detail later. But for now, I’d simply observe that the gospel accounts of Jesus’ trial can be read as confirming the negative image of Pilate.

Pilate’s ultimate responsibility was to oversee Judean affairs, to squash outright rebellion, to keep the tax money flowing to Rome, and, in general, to preserve the fragile peace of the region. And it is this, which, above all, seemed to be at risk when Jesus came to Jerusalem around the feast of Passover. In my next post in this series I’ll examine the peculiar dynamics of Jerusalem in the time of the festival.