He probably doesn’t remember it, but David Dark played a minor role in my journalistic coming-of-age. One of the first assigned articles I ever wrote was for a (now defunct) online magazine called Communique Journal. It was back in 1997 or so, and I was supposed to be doing an interview of the singer/songwriter, Sarah Masen, who happens to be David’s wife. When a snowstorm prevented Sarah from performing the concert that was bringing her to my area, David helped me facilitate an email interview with her. It was my first interview using that bold new form of communication. And it led to my first online publication.

He probably doesn’t remember it, but David Dark played a minor role in my journalistic coming-of-age. One of the first assigned articles I ever wrote was for a (now defunct) online magazine called Communique Journal. It was back in 1997 or so, and I was supposed to be doing an interview of the singer/songwriter, Sarah Masen, who happens to be David’s wife. When a snowstorm prevented Sarah from performing the concert that was bringing her to my area, David helped me facilitate an email interview with her. It was my first interview using that bold new form of communication. And it led to my first online publication.

I’ve kept up with David’s career ever since, and remain a fan of his work (Sarah’s, too). David is an excellent critic of Christianity, religion, and pop culture, and most recently is the author of The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, which proclaims that asking difficult questions about faith is a sacred obligation. Eugene Peterson has called him “a reliable lie detector” when it comes to the Christian faith.

Despite being a busy teacher and while pursuing a PhD in religious studies at Vanderbilt, David was gracious enough to deliver his own thought-provoking (and question-inducing) contribution to our “Voices of Doubt” series.

————-

I can’t recall a time when I haven’t felt my pulse quicken upon entering the lobby of a

movie theater, and I occasionally wonder if other filmgoers feel the same way. For my

part, the powerfully good vibrations hark back to the dream job I took up the day I turned

16, the day I got paid to pass time in what was to me a sacred space. I would soon be

promoted to handling popcorn, selling tickets, and, in time, running the film projector,

but not without a few weeks undergoing the initiatory rite of sweeping my way around

the lobby. There was nothing like it. I’d walk around the lobby with my broom and talk

to strangers about the movies in which they’d recently found themselves immersed. To

my ongoing delight, they were very up for talking. Whether the film they’d seen was

revelatory or lame, they were, in fact, eager to talk it all out with somebody, anybody,

who wanted to know what they thought. There I stood in an awkward fitting vest, horn-rimmed glasses, and a broom in hand. “What’d you think?” I asked (It was my job after

all). Did they sense something of their own lives in what they just experienced? Is the

world a slightly different place now? If so, how?

Movies, I found, related easily to all other movies and the subject of movies was and

is — we know it’s true — absolutely everything. Inspiringly broad-ranging conversations

materialized within seconds, and these conversations knew no boundaries. Everything

had to do with everything else. Movie talk makes for many a tangent. And the tangents,

I came to understand, are the sunshine. The walls came down.

In the wake of a good

movie, the words that work like walls (religion, politics, entertainment, spirituality, or

whatever boundary might keep some aspect of life seem irrelevant to another) would fail

at every turn. They were just different words that couldn’t do justice to the film-viewing

experience. Movies would every so often almost succeed in nailing down our always-slippery human existence. Standing there in the theater lobby, yakking away with people

who wouldn’t normally have a good reason to talk to me, I came to love this slipperiness.

The slipperiness was there in any good movie. It was evident in everything we have from

Shakespeare. And if I could let the thing speak beyond the bounds of church buildings on

Sunday mornings, it was shockingly evident, alive and signalling — this slipperiness — in

my reading of the Bible.

I know this isn’t everyone’s experience with what we sometimes call “a religious

upbringing.” But as a teenager, it seems I read too many comic books, tuned into too

many Twilight Zone episodes, and listened to too much U2 to ever think the Bible could

render the world less weird or more narrow. For me, the Bible wouldn’t (couldn’t!) function as a sort of answer dispenser like a phone book or a dictionary. The Bible

demanded questions (lots of questions) even as it posed cosmically profound questions to

the lifeworld of anyone who dared to open it up. This leather-bound black hole has a way

of freaking you out forever. It makes space for all manner of strangeness. It means more —

not less —

conversation. More —

not less —

thinking.

Somehow, I developed an appetite for that which drove me to doubt what I thought I

knew. And it was in full possession of this sensibility that I sought out conversations

about the Bible. Because I showed up with the same sense of expectation I’d long felt in movie theaters, I found I’d never meet a Bible study I didn’t like. Strangely, I suppose

I could argue that my years at the movie theater birthed within me a desire for a certain

sacred space I spotted constantly there in the lobby, very often in bookstores, and at least

occasionally within the walls of churches. I call it the space of the talkaboutable. It’s the

space a good story or a good song conjures up most effortlessly.

And, needless to say,

it’s the space I believe Jesus of Nazareth brought with him, in word and deed, in his call

to change our ways of thinking and doing in view of a kingdom to come, the space he

announced in response to questions concerning what he and his disciples were up to — questions he more often than not responded to with (frustrating as it was and is) more

questions. This seems to be the way the work of sacred questioning gets done. With an

eye on the life and liveliness to which Jesus summons us, I’d like to argue that this is our

work too. Think of it as a sacred obligation, a calling, a vocation.

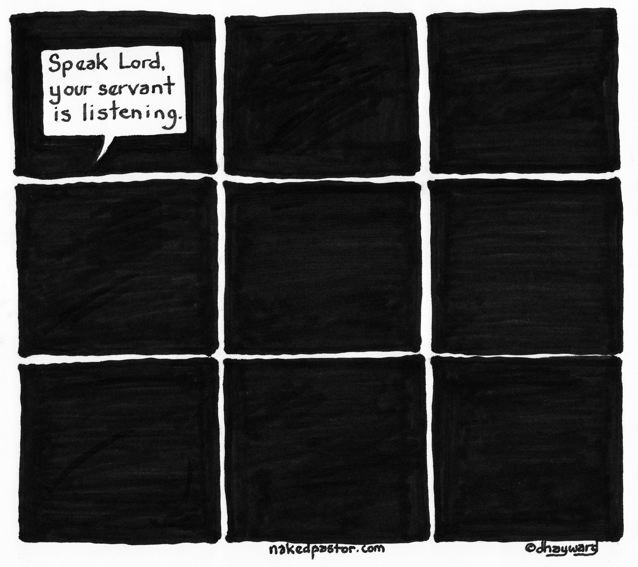

Against the notion that faithfulness to God requires a stifling of our ability to think

things through or that dutiful submission to authority is somehow a virtue in itself,

I’d like to champion the joy, the responsibility, and the thrill of doubting, wondering,

of interrogating the voices (inside and outside our heads) that sabotage our ability to

imagine ourselves and others differently. I believe it might even be the most immediate

means to living a life of proper worshipfulness and due reverence. I have in mind here the

words of Fred Friendly (he worked beside Edward R. Murrow and was played by George

Clooney in the film, Good Night and Good Luck). He said that his job as a newsman was

to create a pain in the viewers’ minds, a pain that can only be relieved by thinking.

Do we bring this sort of thing to our reading of the Bible, our conversations with those

we believe to be like-minded, our consumption of media? If we don’t, I imagine we’re

missing the depths of the abundant life to which we’re called. I believe that it is by the

relentless questioning of ideas, bad ideas about God, money, sex, success patriotism,

and real living people whose names we find it hard to spell, by rethinking the bad ways

we’ve ordered the world in our heads that we redeem and get redeemed. Without it, we

mistake our strongly felt first impressions and often our sense of offendedness itself for

a kind of deep spirituality, as if we’re only called to be simple-minded and deeply upset

by certain people who won’t fit into our grid, our narrow sense of what we find somehow

appropriate and inoffensive.

The Southern storyteller, Flannery O’Connor, once remarked that this thought habit mistakes

Christian faith for a warm, cozy electric blanket that will soothe, dim our perceptions,

and anaesthetize our minds with a stacked deck of ready-made answers. O’Connor

counters this conception by insisting that an engaged and engaging faith is more like a

cross — that lively, more difficult, and more costly interface with the world God so loves.

The questioning I call for is indistinguishable from the call to pay attention to the sweet

old world we’re in, to be mindful of the God-given complexity of the lives before us.

Just as Jesus’ questions worked wonders in human relations, expanding the possibility — the very meaning — of civilization on down to our day with reverberations we have yet

to take on fully, we ourselves are called to celebrate and expand this space.

If we’re to

be faithful to the observational candor the Bible exemplifies and enables, we will push

forward with more — not fewer — questions. It isn’t just that they’re allowed or that God

can handle it. Our commitment to the God’s new day on the way, the kingdom to come,

demands them.

————-

Thanks, David. Keep up with David Dark on twitter or at his blog, Peer Pressure Is Forever. And don’t miss his books The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, The Gospel According to America, and Everyday Apocalypse.

Previous posts in the “Voices of Doubt” series…

• Cara Davis: A Textbook Case

• Matthew Paul Turner: Letting Them See My Doubt

• Sally Lloyd-Jones: Where Did You Put Your Faith?

• Chad Gibbs: When It Doesn’t Seem Fair

• Leeana Tankersley: The Swirling Waters

• Robert Cargill: The Skeptic in the Sanctuary

• Dana Ellis: Haunted by Questions

• Rachel Held Evans on Works-Based Salvation

• Winn Collier: Doubt Better

• Tyler Clark on Losing Fear, Losing Faith

• Rob Stennett on the Genesis of Doubt

• Adam Ellis on Hoping That It’s True

• Nicole Wick on Breaking Up with God

• Anna Broadway on Doubt and Marriage