OK. First off, let’s be clear: I take a philosophical back seat to no one in promoting the right of any American to worship — or not — the God or gods or Force or assorted plants, celestial bodies, etc., of their choice.

And if they don’t believe in any of those things, I don’t have a problem with them putting up billboards, carrying signs or shouting from the public square their convictions as atheists or agnostics, either.

This is America. Within our Constitution and the Bill of Rights are guarantees for both the practice and energetic espousal of religion, and freedom from religious persecution — whether against a particular group of believers, or those who do not believe.

But the pendulum has swung crazily too far when it comes to cries of “separation of church and state” and every American’s right — even those running for elective offices — to live by their religious principles and express them.

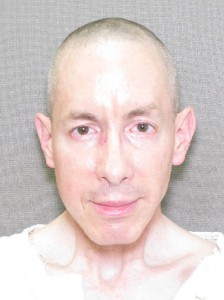

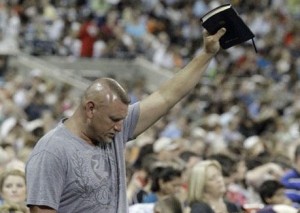

Case in point: This weekend’s stadium prayer event spearheaded by Texas Gov. Rick Perry. He had, apparently, the audacity to look at the nation’s dismal state — a black hole of rising debt that led to an historic loss of the country’s top credit rating, deep unemployment, wars that continue to bleed us of lives and treasure, and a seeming crisis of morals and morale — and call for believers to fast, repent and pray for America.

And, as if throwing gasoline on the already self-immolating critics that arose, he and others had the gall to close their prayers with mention of Jesus. That is what Christians, do, you know – invoke the name of the founder and namesake of their faith. People of other faiths were invited, too. Perhaps there was a conspicuous absence by non-Christians, but that was a choice, too.

But I wonder: would that be any less “offensive” had a Muslim taken the stage to open a public prayer with “In the name of Allah, the most beneficent” and closing them with “O Allah! Accept our invocation”? Or, for that matter, a Rastafarian’s “Blessed is the name of Our Lord God Jah Ras Tafari,” a Hindu’s “We worship the three-eyed One, Lord Shiva,” a Buddhist proclaiming “I take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the supreme Sangha,” a Native American punctuating ritual smoke with “O Great Spirit of our ancestors, I raise my pipe to you,” or a Wiccan chanting “Holy Earth Mother, flesh of the world. . . .”

A chief executive — of a state or of our nation –bringing 30,000 fellow believers to pray in an arena may seem over-the-top today, but leaders calling willing citizens to prayer is hardly new. In our increasingly secularized age, though, anyone who believes in moral absolutes, supports traditional marriage or abhors the millions of potential lives lost to abortion (both interfaith issues, by the way) gets labeled “hater.” Disagree with those stands? No problem, speak out. But it seems when it comes to sharing faith and its values, well, that justifies a tsunami of hyperbole and calls for repression from a vocal minority.

It’s that pesky Constitution and Bill of Rights again, protecting the rights of people to have and express faith, or disbelief, by freely associating and having their place in the public dialog, too.

Officially, presidents have called for a National Day of Prayer every first Thursday in May since 1952. Historically, though, such calls to prayer and fasting go back to George Washington. His successor, President John Adams, renewed that call in 1798. Civil War President Abraham Lincoln, in 1863, called for a day of “national humiliation, fasting and prayer.”

In 1952, President Harry S. Truman institutionalized the Day of Prayer when he signed legislation establishing the annual practice. It has been honored by all succeeding presidents, to varying degrees, since then.

In April of this year, a federal appellate court unanimously dismissed a challenge to the Day of Prayer’s constitutionality, though the Freedom From Religion Foundation continues to attack the event with new filings.

Freedom of association, freedom of expression and freedom of, and from, religion. Believer or skeptic, those rights apply to all.

And there’s this, too: We all have the freedom to not listen or participate or be bludgeoned into accepting either someone’s faith — or someone’s dismissal of faith.

In America, that’s a choice.