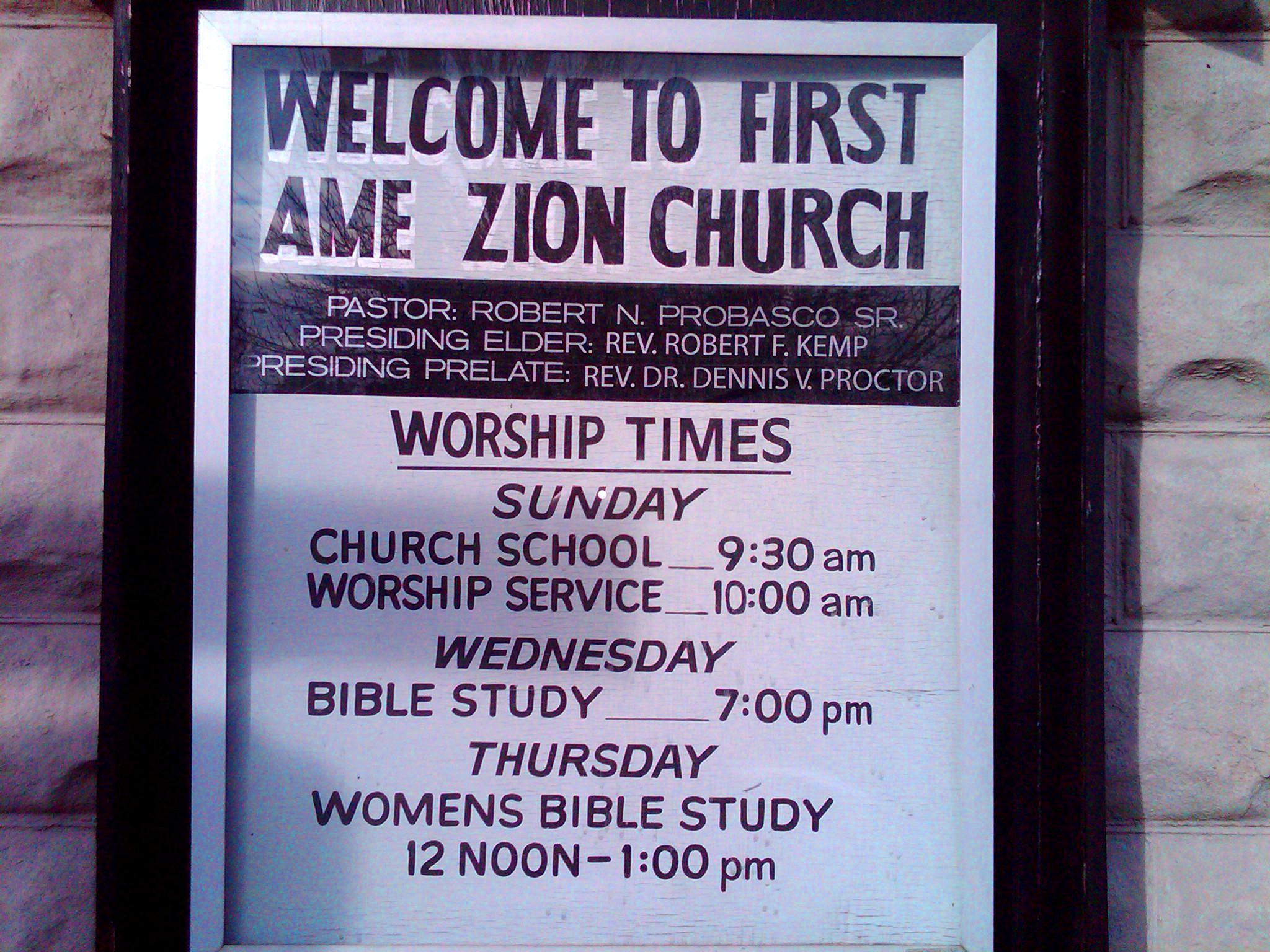

Great church. And it’s fun to say, “Presiding Prelate.” Try it!

James Baldwin, one of my favorite writers – and one of this nation’s best thinkers ever – made a decent living stuffing his books with such pronouncements as: “Love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” Love and fear (but not any connection between the two) were on my mind this morning as Amanda and I shrugged into our church clothes. We were on our way to the First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in North Portland.

Before I go farther, I think you need a little background. I grew up in the working class neighborhoods of North Portland and rubbed shoulders with African Americans and Caucasians all day long. It wasn’t exactly a chorus of We are the World. As a young kid in the early 1970s, I was on the daily receiving end of racial hostility. The arthritis of political correctness hadn’t set in, and racial tensions from the 1960s still ran high. My stepfather had done an excellent job of teaching me to handle conflict by running away and that made me, like any weak member of the heard, a target for bullies, white and black. If they happened to have dark skin, their attacks usually had a racial overtone. I don’t need pity and I don’t feel like a victim. But that’s how it was.

Now, bear in mind that I believe in the ideals of racial equality and wholeheartedly support government programs that would help bring that about. Nevertheless, I hope you understand why, when I walk down the sidewalk and see a group of men of color on the corner, I get an adrenaline fight or flight jolt.

Maybe that can help explain why, as we drove out to what I anticipated to be an all-black church, I turned to Amanda and said, “I’m a little nervous.”

But to be honest, my jitters had nothing to do with any threat of violence or hostility. We were going to church for Christ’s sake.

So I have to give you some more background. I’ve twice visited the non-profit Oregon Food Bank for help getting through the week. Their local pick-up spots—pantries, as they call them—usually operate out of a church basement. One pantry, located off of a side door at Northeast Portland’s Allen Temple, was, on the day I visited, operated by a trio of black women. Church ladies in the best sense of the term. The kind of women who have likely done menial work all their life, have been called the worst names by people who look like me and who know first hand how expensive it is to be poor greeted me with smiles as warm as fresh bread. They got me more than I get myself—and they loved me anyway. If I ever feel the urge to re-embrace Christianity, they’ll be the first to know.

James Baldwin would have understood all this. As a fiercely intelligent, gay, black man in the fifties, he emerged from his experiences with, if you’ll excuse the oxymoron, granite-solid compassion. American blacks, he notes, never wholly swallowed the star-spangled myth of a heroic, democratic melting pot in which the men were all noble bread winners and the women mama bear homemakers. In 1963, he wrote that “Negroes know far more about white Americans than that; it can almost be said, in fact, that they know about white Americans what parents—or, anyway, mothers—know about their children, and that they very often regard white Americans that way.” As he saw it, African Americans are our elders, a source of wisdom informing us about who we are. If you’re white like me, you know, deep down, that this is true—and this is why, even if we feel the urge to run away when we see a black man on the street, we’re more than happy to stop and listen to what he may say through his music or his acting or his stand up comedy. We’re going to him to hear what we need to know about ourselves. Only in America can Morgan Freeman can play God to such ironic, poignant perfection.

And so I was nervous as we drove to the First A.M.E. Zion Church. Not because I would be hated, but because I feared that I would be loved.

And that explains why I sat in the back row with Amanda, regulating my breath, thinking about lunch, playing with her hair—doing anything to avoid bursting into tears. As it happened, today was a special youth day. As we sat in that hundred-year-old converted Masonic lodge with nicked-up wooden pews and dingy stained glass, the kids—mostly teen girls—in jeans and Nikes took over the pulpit. One girl, about 19 or 20, fell to her knees and led the congregation in an improvised prayer—a full ten minutes of gut-wrenching soul outpouring.

And then the preacher took the podium. As irony would have it, the sermon was about fear (AMEN!), which is mentioned 180 times in the Bible, usually as a reassurance from the Lord, as in “Fear not, for I am with you.” (PREACH IT, BROTHER!)

The mixed-race choir was led by a woman sitting at one of those keyboards that switches between honky tonk piano and church organ. In the corner, a drum set sat neglected and unused. I turned to Amanda and said, “Is there a drummer in the house?” But, to be honest, if they’d asked me to sit in, I probably would have declined the opportunity. I probably would have been afraid.