I was giving lectures at Lincoln Christian College in Illinois. I knew of its associations with Lincoln. But what I did not know until I was there is that there was a connection with the Niebuhrs as pastors. Perhaps you know of them– Reinhold Niebuhr, H. Richard Niebuhr (whom I heard lecture when I was at Harvard). The former is of concern in this post for his two most famous books Moral Man and Immoral Society and the equally important The Nature and Destiny of Man.

These books are important today, because President Obama has said that particularly the former has been influential in forming his views on war and peace, and how and whether to combat evil with force, indeed so influential that they seem to have outweighed the influence of Martin Luther King’s pacificism, even though the President cites King as the person who has most influence his views on violence.

When you learn that both Sarah Palin and Newt Gingrich have praised President Obama’s speech in Norway this week, Gingrich even calling it historic, you know something is up, and below, you will find the text of the President’s speech.

There are several things to be said about the speech, which I will do after you read it (below). But before that let me say that President Obama knows and recognizes that he has not yet earned this prize. He says his accomplishments are slight, and many others merited far more than he does. He has accepted it as something he would like to live into, and the prize money of course he is giving entirely to charity. So there should be no more carping about his being awarded the prize— that after all was not his call nor did he solicit such an honor.

What we instead should be focusing on is the substance of the speech itself, which is indeed very substantial and gives us a clue about our President’s views on war and peace, and the rationale for the former. It shows that he was wrestling with the paradox of being the Commander in chief who has his troops in two wars, indeed has just sent more troops into Afghanistan, and yet is accepting this award. Here is the speech itself.

THE PRESIDENT: Your Majesties, Your

Royal Highnesses, distinguished members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee,

citizens of America, and citizens of the world:

I receive this honor with deep gratitude and

great humility. It is an award that speaks to our highest aspirations —

that for all the cruelty and hardship of our world, we are not mere prisoners

of fate. Our actions matter, and can bend history in the direction of

justice.

And yet I would be remiss if I did not

acknowledge the considerable controversy that your generous decision has

generated. (Laughter.) In part, this is because I am at the

beginning, and not the end, of my labors on the world stage. Compared to

some of the giants of history who’ve received this prize — Schweitzer and

King; Marshall and Mandela — my accomplishments are slight. And then

there are the men and women around the world who have been jailed and beaten in

the pursuit of justice; those who toil in humanitarian organizations to relieve

suffering; the unrecognized millions whose quiet acts of courage and compassion

inspire even the most hardened cynics. I cannot argue with those who find

these men and women — some known, some obscure to all but those they help —

to be far more deserving of this honor than I.

But perhaps the most profound issue

surrounding my receipt of this prize is the fact that I am the Commander-in-Chief

of the military of a nation in the midst of two wars. One of these wars

is winding down. The other is a conflict that America did not seek; one

in which we are joined by 42 other countries — including Norway — in an effort

to defend ourselves and all nations from further attacks.

Still, we are at war, and I’m responsible for

the deployment of thousands of young Americans to battle in a distant

land. Some will kill, and some will be killed. And so I come here

with an acute sense of the costs of armed conflict — filled with difficult

questions about the relationship between war and peace, and our effort to

replace one with the other.

Now these questions are not new. War,

in one form or another, appeared with the first man. At the dawn of

history, its morality was not questioned; it was simply a fact, like drought or

disease — the manner in which tribes and then civilizations sought power and

settled their differences.

And over time, as codes of law sought to

control violence within groups, so did philosophers and clerics and statesmen

seek to regulate the destructive power of war. The concept of a

“just war” emerged, suggesting that war is justified only when

certain conditions were met: if it is waged as a last resort or in

self-defense; if the force used is proportional; and if, whenever possible,

civilians are spared from violence.

Of course, we know that for most of history,

this concept of “just war” was rarely observed. The capacity of

human beings to think up new ways to kill one another proved inexhaustible, as

did our capacity to exempt from mercy those who look different or pray to a

different God. Wars between armies gave way to wars between nations —

total wars in which the distinction between combatant and civilian became

blurred. In the span of 30 years, such carnage would twice engulf this

continent. And while it’s hard to conceive of a cause more just than the

defeat of the Third Reich and the Axis powers, World War II was a conflict in which

the total number of civilians who died exceeded the number of soldiers who

perished.

In the wake of such destruction, and with the

advent of the nuclear age, it became clear to victor and vanquished alike that

the world needed institutions to prevent another world war. And so, a

quarter century after the United States Senate rejected the League of Nations

— an idea for which Woodrow Wilson received this prize — America led the

world in constructing an architecture to keep the peace: a Marshall Plan

and a United Nations, mechanisms to govern the waging of war, treaties to

protect human rights, prevent genocide, restrict the most dangerous weapons.

In many ways, these efforts succeeded.

Yes, terrible wars have been fought, and atrocities committed. But there

has been no Third World War. The Cold War ended with jubilant crowds

dismantling a wall. Commerce has stitched much of the world

together. Billions have been lifted from poverty. The ideals of

liberty and self-determination, equality and the rule of law have haltingly

advanced. We are the heirs of the fortitude and foresight of generations

past, and it is a legacy for which my own country is rightfully proud.

And yet, a decade into a new century, this

old architecture is buckling under the weight of new threats. The world

may no longer shudder at the prospect of war between two nuclear superpowers,

but proliferation may increase the risk of catastrophe. Terrorism has

long been a tactic, but modern technology allows a few small men with outsized

rage to murder innocents on a horrific scale.

Moreover, wars between nations have

increasingly given way to wars within nations. The resurgence of ethnic

or sectarian conflicts; the growth of secessionist movements, insurgencies, and

failed states — all these things have increasingly trapped civilians in

unending chaos. In today’s wars, many more civilians are killed than

soldiers; the seeds of future conflict are sown, economies are wrecked, civil

societies torn asunder, refugees amassed, children scarred.

I do not bring with me today a definitive

solution to the problems of war. What I do know is that meeting these

challenges will require the same vision, hard work, and persistence of those

men and women who acted so boldly decades ago. And it will require us to

think in new ways about the notions of just war and the imperatives of a just

peace.

We must begin by acknowledging the hard

truth: We will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes.

There will be times when nations — acting individually or in concert — will

find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified.

I make this statement mindful of what Martin

Luther King Jr. said in this same ceremony years ago: “Violence

never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: it

merely creates new and more complicated ones.” As someone who stands

here as a direct consequence of Dr. King’s life work, I am living testimony to

the moral force of non-violence. I know there’s nothing weak — nothing

passive — nothing naïve — in the creed and lives of Gandhi and King.

But as a head of state sworn to protect and

defend my nation, I cannot be guided by their examples alone. I face the

world as it is, and cannot stand idle in the face of threats to the American

people. For make no mistake: Evil does exist in the world. A

non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler’s armies. Negotiations

cannot convince al Qaeda’s leaders to lay down their arms. To say that

force may sometimes be necessary is not a call to cynicism — it is a

recognition of history; the imperfections of man and the limits of reason.

I raise this point, I begin with this point

because in many countries there is a deep ambivalence about military action today,

no matter what the cause. And at times, this is joined by a reflexive

suspicion of America, the world’s sole military superpower.

But the world must remember that it was not

simply international institutions — not just treaties and declarations — that

brought stability to a post-World War II world. Whatever mistakes we have

made, the plain fact is this: The United States of America has helped

underwrite global security for more than six decades with the blood of our

citizens and the strength of our arms. The service and sacrifice of our

men and women in uniform has promoted peace and prosperity from Germany to

Korea, and enabled democracy to take hold in places like the Balkans. We

have borne this burden not because we seek to impose our will. We have

done so out of enlightened self-interest — because we seek a better future for our children and

grandchildren, and we believe that their lives will be better if others’

children and grandchildren can live in freedom and prosperity.

So yes, the instruments of war do have a role

to play in preserving the peace. And yet this truth must coexist with

another — that no matter how

justified, war promises human tragedy. The soldier’s courage and

sacrifice is full of glory, expressing devotion to country, to cause, to

comrades in arms. But war itself is never glorious, and we must never

trumpet it as such.

So part of our challenge is reconciling these

two seemingly inreconcilable truths — that war is sometimes necessary, and war

at some level is an expression of human folly. Concretely, we must direct our effort to the task that

President Kennedy called for

long ago. “Let us focus,” he said, “on a more practical,

more attainable peace, based not on a sudden revolution in human nature but on

a gradual evolution in human institutions.” A gradual evolution of

human institutions.

What might this evolution look like?

What might these practical steps be?

To begin with, I believe that all nations —

strong and weak alike — must adhere to standards that govern the use of

force. I — like any head of state — reserve the right to act

unilaterally if necessary to defend my nation. Nevertheless, I am

convinced that adhering to standards, international standards, strengthens

those who do, and isolates and weakens those who don’t.

The world rallied around America after the

9/11 attacks, and continues to support our efforts in Afghanistan, because of

the horror of those senseless attacks and the recognized principle of

self-defense. Likewise, the world recognized the need to confront Saddam

Hussein when he invaded Kuwait — a consensus that sent a clear message to all

about the cost of aggression.

Furthermore, America — in fact, no nation —

can insist that others follow the rules of the road if we refuse to follow them

ourselves. For when we don’t, our actions appear arbitrary and undercut

the legitimacy of future interventions, no matter how justified.

And this becomes particularly important when

the purpose of military action extends beyond self-defense or the defense of

one nation against an aggressor. More and more, we all confront difficult

questions about how to prevent the slaughter of civilians by their own

government, or to stop a civil war whose violence and suffering can engulf an entire

region.

I believe that force can be justified on

humanitarian grounds, as it was in the Balkans, or in other places that have

been scarred by war. Inaction tears at our conscience and can lead to

more costly intervention later. That’s why all responsible nations must

embrace the role that militaries with a clear mandate can play to keep the

peace.

America’s commitment to global security will

never waver. But in a world in which threats are more diffuse, and

missions more complex, America cannot act alone. America alone cannot

secure the peace. This is true in Afghanistan. This is true in

failed states like Somalia, where terrorism and piracy is joined by famine and

human suffering. And sadly, it will continue to be true in unstable

regions for years to come.

The leaders and soldiers of NATO countries,

and other friends and allies, demonstrate this truth through the capacity and

courage they’ve shown in Afghanistan. But in many countries, there is a

disconnect between the efforts of those who serve and the ambivalence of the

broader public. I understand why war is not popular, but I also know

this: The belief that peace is desirable is rarely enough to achieve

it. Peace requires responsibility. Peace entails sacrifice.

That’s why NATO continues to be indispensable. That’s why we must

strengthen U.N. and regional peacekeeping, and not leave the task to a few

countries. That’s why we honor those who return home from peacekeeping

and training abroad to Oslo and Rome; to Ottawa and Sydney; to Dhaka and Kigali

— we honor them not as makers of war, but of wagers — but as wagers of peace.

Let me make one final point about the use of

force. Even as we make difficult decisions about going to war, we must

also think clearly about how we fight it. The Nobel Committee recognized

this truth in awarding its first prize for peace to Henry Dunant — the founder

of the Red Cross, and a driving force behind the Geneva Conventions.

Where force is necessary, we have a moral and

strategic interest in binding ourselves to certain rules of conduct. And

even as we confront a vicious adversary that abides by no rules, I believe the

United States of America must remain a standard bearer in the conduct of

war. That is what makes us different from those whom we fight. That

is a source of our strength. That is why I prohibited torture. That

is why I ordered the prison at Guantanamo Bay closed. And that is why I

have reaffirmed America’s commitment to abide by the Geneva Conventions.

We lose ourselves when we compromise the very ideals that we fight to

defend. (Applause.) And we honor — we honor those ideals by

upholding them not when it’s easy, but when it is hard.

I have spoken at some length to the question that

must weigh on our minds and our hearts as we choose to wage war. But let

me now turn to our effort to avoid such tragic choices, and speak of three ways

that we can build a just and lasting peace.

First, in dealing with those nations that

break rules and laws, I believe that we must develop alternatives to violence

that are tough enough to actually change behavior — for if we want a lasting

peace, then the words of the international community must mean something.

Those regimes that break the rules must be held accountable. Sanctions

must exact a real price. Intransigence must be met with increased

pressure — and such pressure exists only when the world stands together as

one.

One urgent example is the effort to

prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, and to seek a world without them.

In the middle of the last century, nations agreed to be bound by a treaty whose

bargain is clear: All will have access to peaceful nuclear power; those

without nuclear weapons will forsake them; and those with nuclear weapons will

work towards disarmament. I am committed to upholding this treaty.

It is a centerpiece of my foreign policy. And I’m working with President

Medvedev to reduce America and Russia’s nuclear stockpiles.

But it is also incumbent upon all of us to

insist that nations like Iran and North Korea do not game the system.

Those who claim to respect international law cannot avert their eyes when those

laws are flouted. Those who care for their own security cannot ignore the

danger of an arms race in the Middle East or East Asia. Those who seek

peace cannot stand idly by as nations arm themselves for nuclear war.

The same principle applies to those who

violate international laws by brutalizing their own people. When there is

genocide in Darfur, systematic rape in Congo, repression in Burma — there must

be consequences. Yes, there will be engagement; yes, there will be

diplomacy — but there must be consequences when those things fail. And

the closer we stand together, the less likely we will be faced with the choice

between armed intervention and complicity in oppression.

This brings me to a second point — the

nature of the peace that we seek. For peace is not merely the absence of

visible conflict. Only a just peace based on the inherent rights and

dignity of every individual can truly be lasting.

It was this insight that drove drafters of

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights after the Second World War. In

the wake of devastation, they recognized that if human rights are not protected,

peace is a hollow promise.

And yet too often, these words are

ignored. For some countries, the failure to uphold human rights is

excused by the false suggestion that these are somehow Western principles,

foreign to local cultures or stages of a nation’s development. And within

America, there has long been a tension between those who describe themselves as

realists or idealists — a tension that suggests a stark choice between the

narrow pursuit of interests or an endless campaign to impose our values around

the world.

I reject these choices. I believe that

peace is unstable where citizens are denied the right to speak freely or

worship as they please; choose their own leaders or assemble without

fear. Pent-up grievances fester, and the suppression of tribal and

religious identity can lead to violence. We also know that the opposite

is true. Only when Europe became free did it finally find peace.

America has never fought a war against a democracy, and our closest friends are

governments that protect the rights of their citizens. No matter how

callously defined, neither America’s interests — nor the world’s — are served

by the denial of human aspirations.

So even as we respect the unique culture and

traditions of different countries, America will always be a voice for those

aspirations that are universal. We will bear witness to the quiet dignity

of reformers like Aung Sang Suu Kyi; to the bravery of Zimbabweans who cast

their ballots in the face of beatings; to the hundreds of thousands who have

marched silently through the streets of Iran. It is telling that the

leaders of these governments fear the aspirations of their own people more than

the power of any other nation. And it is the responsibility of all free

people and free nations to make clear that these movements — these movements

of hope and history — they have us on their side.

Let me also say this: The promotion of

human rights cannot be about exhortation alone. At times, it must be

coupled with painstaking diplomacy. I know that engagement with

repressive regimes lacks the satisfying purity of indignation. But I also

know that sanctions without outreach — condemnation without discussion — can

carry forward only a crippling status quo. No repressive regime can move

down a new path unless it has the choice of an open door.

In light of the Cultural Revolution’s

horrors, Nixon’s meeting with Mao appeared inexcusable — and yet it surely

helped set China on a path where millions of its citizens have been lifted from

poverty and connected to open societies. Pope John Paul’s engagement with

Poland created space not just for the Catholic Church, but for labor leaders

like Lech Walesa. Ronald Reagan’s efforts on arms control and embrace of

perestroika not only improved relations with the Soviet Union, but empowered

dissidents throughout Eastern Europe. There’s no simple formula

here. But we must try as best we can to balance isolation and engagement,

pressure and incentives, so that human rights and dignity are advanced over

time.

Third, a just peace includes not only civil

and political rights — it must encompass economic security and

opportunity. For true peace is not just freedom from fear, but freedom

from want.

It is undoubtedly true that development

rarely takes root without security; it is also true that security does not

exist where human beings do not have access to enough food, or clean water, or

the medicine and shelter they need to survive. It does not exist where

children can’t aspire to a decent education or a job that supports a

family. The absence of hope can rot a society from within.

And that’s why helping farmers feed their own

people — or nations educate their children and care for the sick — is not

mere charity. It’s also why the world must come together to confront

climate change. There is little scientific dispute that if we do nothing,

we will face more drought, more famine, more mass displacement — all of which

will fuel more conflict for decades. For this reason, it is not merely

scientists and environmental activists who call for swift and forceful action

— it’s military leaders in my own country and others who understand our common

security hangs in the balance.

Agreements among nations. Strong

institutions. Support for human rights. Investments in

development. All these are vital ingredients in bringing about the

evolution that President Kennedy spoke about. And yet, I do not believe

that we will have the will, the determination, the staying power, to complete

this work without something more — and that’s the continued expansion of our

moral imagination; an insistence that there’s something irreducible that we all

share.

As the world grows smaller, you might think

it would be easier for human beings to recognize how similar we are; to

understand that we’re all basically seeking the same things; that we all hope

for the chance to live out our lives with some measure of happiness and

fulfillment for ourselves and our families.

And yet somehow, given the dizzying pace of

globalization, the cultural leveling of modernity, it perhaps comes as no

surprise that people fear the loss of what they cherish in their particular

identities — their race, their tribe, and perhaps most powerfully their

religion. In some places, this fear has led to conflict. At times,

it even feels like we’re moving backwards. We see it in the Middle East,

as the conflict between Arabs and Jews seems to harden. We see it in

nations that are torn asunder by tribal lines.

And most dangerously, we see it in

the way that religion is used to justify the murder of innocents by those who

have distorted and defiled the great religion of Islam, and who attacked my

country from Afghanistan. These extremists are not the first to kill in

the name of God; the cruelties of the Crusades are amply recorded. But

they remind us that no Holy War can ever be a just war. For if you truly

believe that you are carrying out divine will, then there is no need for

restraint — no need to spare the pregnant mother, or the medic, or the Red

Cross worker, or even a person of one’s own faith. Such a warped view of

religion is not just incompatible with the concept of peace, but I believe it’s

incompatible with the very purpose of faith — for the one rule that lies at

the heart of every major religion is that we do unto others as we would have

them do unto us.

Adhering to this law of love has always been

the core struggle of human nature. For we are fallible. We make

mistakes, and fall victim to the temptations of pride, and power, and sometimes

evil. Even those of us with the best of intentions will at times fail to

right the wrongs before us.

But we do not have to think that human nature

is perfect for us to still believe that the human condition can be

perfected. We do not have to live in an idealized world to still reach

for those ideals that will make it a better place. The non-violence

practiced by men like Gandhi and King may not have been practical or possible

in every circumstance, but the love that they preached — their fundamental

faith in human progress — that must always be the North Star that guides us on

our journey.

For if we lose that faith — if we dismiss it

as silly or naïve; if we divorce it from the decisions that we make on issues

of war and peace — then we lose what’s best about humanity. We lose our

sense of possibility. We lose our moral compass.

Like generations have before us, we must

reject that future. As Dr. King said at this occasion so many years ago,

“I refuse to accept despair as the final response to the ambiguities of

history. I refuse to accept the idea that the ‘isness’ of man’s present

condition makes him morally incapable of reaching up for the eternal

‘oughtness’ that forever confronts him.”

Let us reach for the world that ought to be

— that spark of the divine that still stirs within each of our souls.

(Applause.)

Somewhere today, in the here and now, in the

world as it is, a soldier sees he’s outgunned, but stands firm to keep the

peace. Somewhere today, in this world, a young protestor awaits the

brutality of her government, but has the courage to march on. Somewhere

today, a mother facing punishing poverty still takes the time to teach her

child, scrapes together what few coins she has to send that child to school —

because she believes that a cruel world still has a place for that child’s

dreams.

Let us live by their example. We can

acknowledge that oppression will always be with us, and still strive for

justice. We can admit the intractability of depravation, and still strive

for dignity. Clear-eyed, we can understand that there will be war, and

still strive for peace. We can do that — for that is the story of human

progress; that’s the hope of all the world; and at this moment of challenge,

that must be our work here on Earth.

Thank you very much. (Applause.)

———————————-

Two things stand out about this speech for me. Firstly, what President Obama is actually talking about is not a ‘just war’ but when a war is justifiable because the alternatives are morally worse. This is precisely the kind of tough critical moral thinking that is required in the age in which we live. He acknowledges as much when he distinguishes between what he calls a just war… and the concept of Jihad or Holy war, a war that justifies any kind of behavior in the name of God. Here is how he puts it—-

“But

they remind us that no Holy War can ever be a just war. For if you truly

believe that you are carrying out divine will, then there is no need for

restraint — no need to spare the pregnant mother, or the medic, or the Red

Cross worker, or even a person of one’s own faith. Such a warped view of

religion is not just incompatible with the concept of peace, but I believe it’s

incompatible with the very purpose of faith — for the one rule that lies at

the heart of every major religion is that we do unto others as we would have

them do unto us.”

I quite agree with him about this, but the converse is also true. No so-called just war can be considered or actually be a holy war. As he says earlier in the speech, war should never be glorified, especially when at best it is the lesser of several evils, not the greater of several goods. What can and should be honored is the sacrifices made in war by soldiers or civilians for the sake of saving others lives. This should always be honored, without glorifying war. I am mindful of what Robert E. Lee once said— “it is a good thing that war is so terrible, or else we might love it too much.”

Indeed, we should not love it at all, especially if we serve the Prince of Peace, for as President Obama admits, in all recent wars in which counting has been done in any meaningful manner—- more civilians were killed than soldiers. And it is completely without merit to trivialize civilian casualties as ‘collateral damage’.

No human being created in God’s image and of sacred worth should ever be reduced to a mere number or called ‘collateral damage’. These are the kind of reductionistic approaches to other peoples lives that allow warlords to justify all sorts of unjust behavior in the name of some apparently or supposedly good cause.

And I quite agree with President Obama that only a warped view of Biblical religion could lead to a belief in a doctrine of holy war as carried out by fallible sinful human beings. Fallen human beings are incapable of carrying out a holy war, incapable of making the necessary moral distinctions so that right is always done in any given situation, or at least so that there are more rescued victims of injustices than newly created victims in the course of a war.

But I must confess to being doubtful even when we talk about a justifiable struggle that it ever becomes a just war. For what the President has admitted in this speech is that war is not merely hell, it is one of the ultimate expressions of human sin on earth, one of the greatest expressions of a violation of love of neighbor and even love of enemy imaginable.

Even if a convincing case could be made for a war of necessity, say WWII, it still involved so much killing of non-combatants, so much taking of innocent life, that as a Christian I have to insist that the most appropriate and necessary response to the conclusion of a war is not a victory parade, but a service of repentance for sin on a grand and grotesque scale. The sacrifices of the soldiers should be recognized, their safe return should be prayed for and thanked God for, but not without recognizing that we have asked them to go and do something that inevitably involves commiting sin on a grand scale! And such actions do indeed require repentance.

There are no clear cut winners in a war— its just that some lose less than others, some lose less permanently than others. As one of my favorite poets once said “any man’s death diminishes me, for I am a part of mankind. Therefore do not seek to know for whom the bell, the death knell tolls— it tolls for thee.”

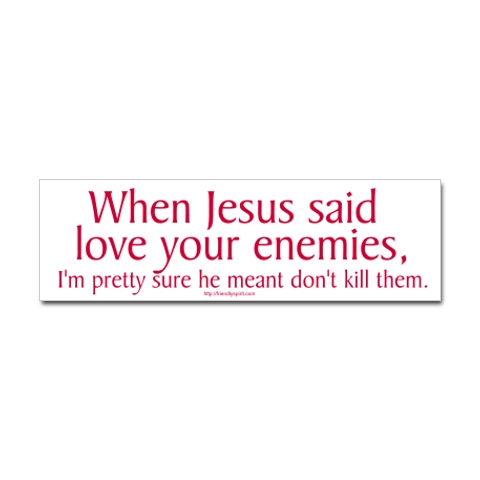

And as for what Jesus thinks about this matter…. I leave you with a recent bumpersticker that lets us know……