We spent today at the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania, which is out in the northwestern part of Philadelphia. Julie loves horticulture, and has been wanting to get out there for some time. There was a performance of Japanese taiko drummers from Swarthmore College that we wanted to see, which is what got me and the kids interested in going. The performance was pretty great, as it turned out, but what surprised me greatly was how much I loved the arboretum itself. We bought a family membership on the spot.

Earlier this week, in a post titled “The Impermanence of Things,” I wrote about the tiny cabin in the country where my great-great-aunts Lois Simmons and Hilda Simmons Moss lived out the final years of their lives, and how their home, now long gone, was a haven for me as a small boy. Lois was an accomplished amateur horticulturist, and tended a remarkable garden. Here is a photograph of their cabin:

Those are fragrant sweet olive trees framing the porch. What you can’t see from this view is the giant magnolia tree in the front yard, the magnolia fuscata tree with blossoms that smelled of banana, the dogwoods, the four o’clocks. On the right side of the cabin, behind the garage, were camellia bushes. A narrow path led around the left side of the house, to a bamboo stand, and beds of purple-blue phlox. If you took another path, you’d pass Loisie’s compost pile, next to the place where her favorite cats were buried, and emerge into a small field, much of which was covered with daffodils, King Alfreds, spidery red lycorises, and above all, jonquils. That field was enclosed by cedars, gum trees, pin oaks and even a chestnut, among other trees. I seem to recall a venerable pear tree in the field, one we had to be careful walking near when fruit was on the ground, because the sweet rotting pears were a favorite of bees.

When I was a small boy — 3, 4, 5 and 6 years old — I spent a lot of time with Loisie in these gardens (here’s a photo of her in her kitchen during those years).

I would walk alongside my elderly aunt, who wore a thin cotton dress and an ever-present green visor, and steadied herself with a dried bamboo staff. And we would talk. She would tell me about her plants, her cats, and the birds who came into her garden. Lois had lived a life that seemed dramatic to a country child like me. When she and Hilda were young, they were Red Cross nurses serving in the canteen in Dijon during the Great War. Lois later lived in Honduras (I used to say the word “Tegucigalpa,” her town, over and over, because it tasted so exotic in my mouth), and would tell me about iguanas that used to sun themselves on her lawn there. She spent her years before moving to the country in New Orleans. I want to say she lived on Esplanade Avenue, but I’m not sure. I do know that I heard her speak of Esplanade Avenue, and it sounded so magical to me: Esplanade Avenue. Lois introduced me to so many words that delighted and entranced me.

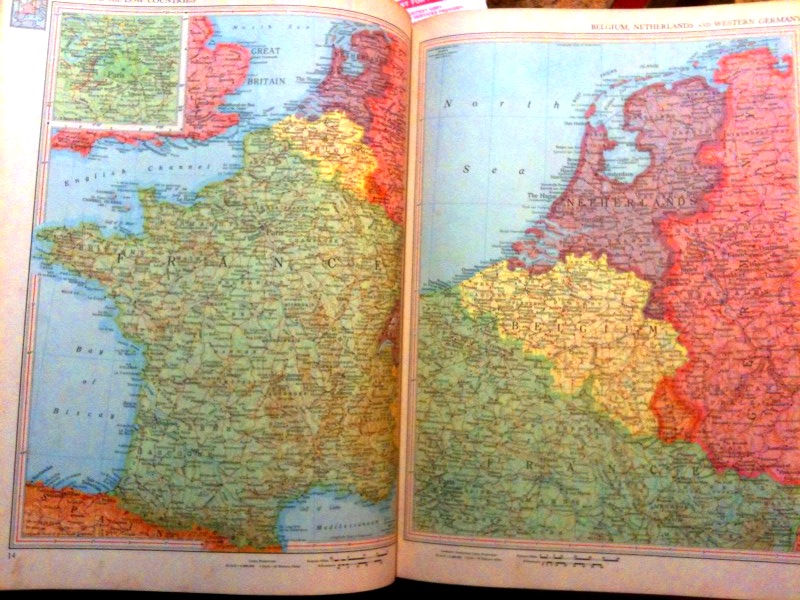

I would walk alongside my elderly aunt, who wore a thin cotton dress and an ever-present green visor, and steadied herself with a dried bamboo staff. And we would talk. She would tell me about her plants, her cats, and the birds who came into her garden. Lois had lived a life that seemed dramatic to a country child like me. When she and Hilda were young, they were Red Cross nurses serving in the canteen in Dijon during the Great War. Lois later lived in Honduras (I used to say the word “Tegucigalpa,” her town, over and over, because it tasted so exotic in my mouth), and would tell me about iguanas that used to sun themselves on her lawn there. She spent her years before moving to the country in New Orleans. I want to say she lived on Esplanade Avenue, but I’m not sure. I do know that I heard her speak of Esplanade Avenue, and it sounded so magical to me: Esplanade Avenue. Lois introduced me to so many words that delighted and entranced me.And so many worlds too. I have written in this space before about how Lois and Hilda would sit with little me on their red-leather couch, a 1951 Rand McNally atlas splayed across my lap, drawing routes on the map with my index finger, and telling me what we were seeing as we passed through those places. I still have that atlas, with my childish writing in pencil on some pages. Here is the actual pages of France and the Low Countries, where we did most of our imaginative traveling.

They took me with them to the Red Cross canteen the night Gen. Pershing showed up unannounced, and Lois, unable to find the key to the pantry, had to strain the general’s tea through her petticoat. I was there with Hilda on the Champs-Elysees when the Armistice was announced, and a Frenchman grabbed her and gave her such a kiss. I was also with them on the nearby plantation they grew up on after the turn of the century, the daughters of one of the plantation managers. They introduced me to the black sharecropper who wouldn’t wear shoes, and who struck matches on the callused soles of his feet. I met their late brother Clint, a whiskey fiend whose faithful old horse knew the way home to the country, six miles south of the saloon in town, when Clint was passed out in the saddle. These were the worlds they gave me, in a time in my life when these stories entered my mind with the power of myth to shape the course of my life.

Lois’s signature is inscribed indelibly on the margins of my life’s passages. Many of these mythic stories came to me by the fireplace in their cabin. Others they passed on to me in the rocking chairs on their front porch. But some came to me from Lois as we walked together in her hidden gardens, under the Chinese rain tree, amid the japonicas, the magnolias, the bamboo, the wisteria vines, the spidery red lycoris, the daffodils and, above all, the sweet, sweet jonquils.

Jonquils like those I saw in the grove today.

That grove was not like anything in Loisie’s garden, but it did have a quality of … enclosure that brought to mind how it felt to be in Loisie’s world when I was a boy. There was nowhere else like it. She cast a spell on me, and taught me about wonderful things. She showed me the old speckled king snake who lived in the bushes under her magnolia grandiflora, and told me he was our friend. When I walked to Loisie’s with a neighbor boy one summer afternoon, and saw the old king snake stretched out sunning himself in the pea gravel lane in front of the cabin, my buddy froze in fear, but I stepped gingerly over the snake, unafraid. Loisie said he was a friend, and inasmuch as she was the happy genius of this garden, who was I to doubt her?

Lois and Hilda are long gone, as is their cabin, their gardens, the orchard, all of it. I have memories, and a few relics of that world: a pale green Depression glass bowl that Loisie mixed cupcakes and pecan cookies in, that Rand McNally atlas, and a 1768 color print of Taylor birds and fruit that hung on the cabin wall. If we were fortunate enough to have a grove of wonderment in which to hide during our childhoods, I think we spend the rest of our lives trying to get back there. Sometimes, we stumble upon fragments of them, serendipitously, in unlikely places. And that is a grace.

It’s no surprise that this is on my mind these days. My sister Ruthie, who’s fighting cancer, lives in a house she and her husband built in what was the far edge of Loisie’s orchard. In her yard is one of Loisie’s camellia bushes, still blooming after all these years.

UPDATE: On further reflection, prompted by good comments from MargaretE and Rombald, the perfectly obvious whapped me in the face: I was exiled from the “sacred grove” of my early youth by the passage of time, and by the death and decay that comes with it (Aunt Lois passed away, and Aunt Hilda moved to a nursing facility, and later died). I long deeply to return to that state of paradise and enchantment and security. Just like Adam and Eve with Eden. Genesis is the story of all sorrowful humanity.